Artists Stella Lai and Jason Jagel show their playful sides at Nathan Larramendy Gallery in Ojai

(ventura county reporter) “He wanted revenge because I killed his cat,” says artist Stella Lai. “I saw his show,” she says of artist, Jason Jagel, “and he had this video where he has a cat character that has wings, [similar] to my earlier works aesthetically, which were influenced by Japanese animation and Chinese pop culture. So I decided to draw my cat, and kill his cat, and paint it in this panel and mail it to him. I didn’t expect that he would go in and draw [a response].”

(ventura county reporter) “He wanted revenge because I killed his cat,” says artist Stella Lai. “I saw his show,” she says of artist, Jason Jagel, “and he had this video where he has a cat character that has wings, [similar] to my earlier works aesthetically, which were influenced by Japanese animation and Chinese pop culture. So I decided to draw my cat, and kill his cat, and paint it in this panel and mail it to him. I didn’t expect that he would go in and draw [a response].”

“She painted it note-perfectly,” says Jagel. “In response, I painted buck teeth on her cat girl, and this character who has his hand down [the girl’s] shirt.”

All of this is by way of explanation for the wood panel painting, Jason, Sorry, but Your Cat Must Die! Stella. The small, unassuming prank shows the playful collaboration between Lai and Jagel. The piece is part of their exhibitions, I Love My Foreigner Friends and Flesh of My Skin, at Nathan Larramendy Gallery in Ojai.

“Jason, Sorry” is the only piece hanging that the two created together, but the installation itself is the result of a two-day artistic jam the two undertook. Both exhibitions hung at the Queen’s Nails Annex gallery in San Francisco, but separately. The Larramendy exhibition allows for a more subtle interplay between the two artists’ work.

As Jagel explains it, Lai’s artistic note-passing was emblematic of their working relationship.

“I sent her a note with a little picture that said, ‘Dear Stella, Math is great.’ I felt like we were two kids that would have met in fourth grade and just had a fun time goofing around doing math together,” says Jagel.

The math comparison initially seems at odds with the whimsical nature of the wall’s flourishes, including colorful combinations that bring to mind the Asian pop culture influences Lai mentioned. Owner Nathan Larramendy points to a dewdrop that contrasts against a solid brown tree trunk. The drop was Lai’s, and the little man inside, curled up within the womblike detail and staring at porn, is Jagel’s work.

“Stella and I were definitely having a conversation,” Jagel says.

The common thread in this conversation appears to be social critique.

Hong Kong-born Lai explores the reconciliation of spirituality with the Western-influenced pop culture in Chinese society. She specifically criticizes the trendy practice, prevalent among young women, of trying to look more Caucasian.

In Hong Kong, Lai notes a disturbing worship of all features white or Anglo. Because the country is so small, culture is figuratively and quite literally cramped. In a society with a heavy colonial background, the obsession with imitating The Other — in this case, Anglo —prompts discussion.

“Growing up in Asia, it’s just compact,” Lai says. “With these types of images constantly in media and everywhere, you don’t even have the room to remove yourself and criticize it.”

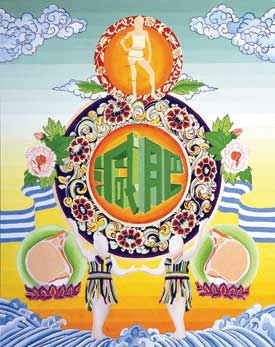

In Lai’s paintings, the highly marketed freak show of thinning creams and breast augmentation plays out against a backdrop of recognizably Asian textiles. In pieces like “White” and “Eat!” the figure in the foreground, an Anglicized Asian ideal of beauty, appears before symbols inspired by Tibetan thangka paintings. This demigoddess might be considering a move from an A-cup to a C-cup, or the cruel paradox of a thin-obsessed society whose streets are filled with anxious street vendors, hawking local delicacies.

It is fitting that the ancient and sacred butt up against the ungodly practice of body manipulation and a dogged pursuit of Western aesthetics. It is no coincidence that the would-be heroine of Lai’s “White” is an auburn-tressed nymphet whose skin has been bleached so completely, she’s in danger of being whitewashed and airbrushed out of existence.

“Materialism is replacing spirituality in society,” Lai observes.

While Lai uses traditional iconography as a springboard for her work, Jagel identifies with the “post-Crumb, post-underground [comic art] of the late ’80s and early ’90s.” In “Sorry, Jason” he eschews the formal world of panels for a freer-flowing, non-linear form.

It is an interesting departure for someone who identifies so closely with the comic style. In place of the conventional panels, he said his pieces are “kind of exploded, spread out all over the place.”

Playfully classifying himself as a “failed comic artist,” Jagel doesn’t mind that his paintings take more than a quick glance to absorb. They depict lush worlds of urban complexity and all the requisite suffering of a multilevel metropolis. Absent a superhero, real-world vignettes play out as still scenes scattered throughout the spread. One piece, “The Artist In No Way Endorses or Condones Violence Against Law Officials,” spills over two framed canvases. The works are complicated, Where’s Waldo?-esque scenes of citizens on the verge, engaging vices.

Although he might avoid the staid and painstaking world of comic strips, Jagel created a small graphic novel in the form of a fold-out, accordion-style chap book, “Flesh of My Skin.” The frenetic black and white world acts as a narrative puzzle and is accompanied by a CD of vintage murder ballads, spoken word and reggae.

The titles of his paintings challenge the observer by offering an angle rather than a grand summary or classification, and most of his concepts spring from doodling rather than pre-planning. To Jagel, disjointed thought makes for good narrative.

“I believe … in this kind of bastard voice, this unholy abomination type of voice,” says Jagel. “In our culture today, no one is really pure of creation or spirit.”