Meet John Wilcock, the veteran travel writer, rabble-rouser, and alternative press icon who lives down the block

(ventura county reporter) John Wilcock drops an anecdote about Norman Mailer.

(ventura county reporter) John Wilcock drops an anecdote about Norman Mailer.

“We never really got along very well,” considers the 78 year-old. “I suppose it was understandable. He was still young — in his early 20s — when he wrote the The Naked and the Dead. He sounded a bit self-important. I suppose it’s understandable in retrospect.”

Wilcock was a seasoned journalist with a résumé spanning three countries when he found himself spending his Thursday nights with Mailer and a printing press. “He would arrive last-minute with his column. You couldn’t cut a word of it,” remembers Wilcock, who was secretly tickled when Mailer’s use of “nuance” became “nuisance” by virtue of bad typesetting.

It was 1955, and the Village Voice — the precursor to the alternative newsweekly as we know it — was in its maiden year, founded, as the story goes, by Jerry Tallmer, (who would later institute the Obie Award for off-Broadway theater), financier Ed Fancher, New School professor Dan Wolf and Mailer.

But Wilcock was there, too. He would later tell fellow countryman Ian Soutar in a 2004 interview for his old employer, The Sheffield Telegraph, that the powerful foursome put up money to finance the paper, but he did not, thus explaining why he isn’t often counted as one of the paper’s founders. Wilcock does have the distinction of receiving the first byline to run on a Voice cover and his column, “The Village Square,” ran in the debut issue. (The pun was perhaps intentional; Wilcock, a thirtysomething during alternative media’s prime, looked at himself as “probably the oldest person in underground press.”)

An underground celebrity might sound like an oxymoron. By definition, early alternative press skirted the mainstream, yet its heyday — approximately 1966 to 1971 — highlighted a considerable crop of luminaries, like satirist Paul Krassner and Yippie Abbie Hoffman.

But a 1973 New York Times profile, entitled, “At Home with John Wilcock, an Influential Man Nobody Knows,” proclaimed, “Wilcock is still in the underground.” A 1991 profile in the British Independent noted, “He has an ability to make no money like others have an ability to make lots of it.”

As of this writing, Wilcock has even escaped a Wikipedia entry.

Despite a successful career as travel writer and his ubiquitous presence in the underground press engines (he often recalls being at the right place at the right time), the Independent piece argued that Wilcock had yet to become a household name. Little has changed; he still writes “a quarter of a million words” a year, by his estimation, but there’s a sense that perhaps he has avoided lasting commercial success — and its byproduct, financial security — by maintaining underground ideals.

Now the Briton who sat in all the right living rooms beside all the right visionaries and lived to write millions of words around it is at peace living in a guesthouse that borders orchards in Ojai. He wears a maroon grandpa-style sweater. (The Independent described his dress sense as “famously horrible” and “arranged as if to promote the virtues of nudism,” but if that’s the case, with the exception of bright yellow socks, I think he’s slipping.) He serves up coffee on his patio, and after a conversation that touches on everything from the design flaws in a Sony Handycam to favorite living artists (he’s a fan of Christo of yellow umbrella fame), he suggests a stroll over to the horses.

And through it all, with a Northern English accent that sounds nothing short of distinguished and gentlemanly to Californian ears, Wilcock seems only mildly, occasionally annoyed that few people have heard of him.

An unfinished life?

Wilcock’s career has involved an eclectic mix of traditional daily newspapers, celebrity interviews and radical columns, so it’s fitting that his 65,000-word autobiography reads like a series of essays. This did nothing to win him any book deals, however — the majority of editors who passed on his memoir cited its less-than-fluid format. Wilcock sees nothing wrong with the way the book is sewn together but, having let it rest for nearly a decade, says he is always looking for an editor to take it on, ultimately to share the profit.

A few editors criticized Wilcock for not writing about his childhood. This was nearly ten years ago.

“At the time, Angela’s Ashes was popular,” he remarks with a flicker of distaste.

But Wilcock says his story begins in New York in the 1950s “partly because I don’t remember anything before that, partly because I believe my life began in the ’50s, ’60s. There’s nothing of consequence before that — it was just training, becoming a travel writer, writing travel books, magic, basically.”

The inconsequential period, then, spanned his life in Sheffield, England, where he left school at the age of 16 — “it was much less of a tradition to go on to college in England, it wouldn’t have done me any good” — and went straight to The Sheffield Telegraph.

This would explain his arguably radical philosophy on schooling. “When kids leave school, they should be granted a certain amount of money — $5,000, maybe — and expelled from the country. When they come back, they have [college] credits, and can learn what they want.” He pauses. “Things you think are outrageous, in a few years’ time are commonplace.”

Before he ventured far from home himself, he was trained in the nitty gritty of news writing by working as a cub reporter in Northern England. “One of the things about learning to put a story together very quickly, you would call people up and dictate [the story] to people who sat at typewriters and were usually short-tempered and very rude. You learned writing a story and dictating it clearly.”

After three years of this, he moved on to The Daily Mail (currently at a circulation of two million), then The Daily Mirror.

He describes himself as a “tight writer, trained on tabloid that was still paper-rationed.”

Wilcock wasn’t driven from his homeland due to any external forces but, rather, believed that there was very little personal progress he could make in England. His ensuing career as an underground publisher, travel writer and “witch’s apprentice” generally reinforces the notion that the stereotypically more strait-laced United Kingdom wasn’t for him.

“I got kind of really fed up with England,” he recalls, “and I read in Time magazine about Canada,” which he calls “a country that’s like America but it’s English!”

Arriving in Toronto, he worked as a typist for the Greater Toronto Area Credit Bureau, then landed a job at United Press International. He met Canadian millionaire and sports entrepreneur Jack Kent-Cooke at a press conference and impressed him with his London-based journalism résumé.

Kent-Cooke was pleased at Wilcock’s decision to move to New York City. Wilcock became the go-to man for interviews with Marilyn Monroe, Marlene Dietrich and, in Los Angeles, Milton Berle, Rock Hudson and Leonard Bernstein while on assignment for the Kent-Cooke-owned magazines Saturday Nite and Liberty.

And then came the Voice.

In an examination of the underground press that ran in the August 1967 issue of Playboy, Jacob Brackman credited the Voice for constructing “its civilizing bridge between the most gifted of the underground” and “the establishment’s legitimate frontier.”

Even as a struggling alternative weekly, the Voice was tame by the standards of many on the left side of the spectrum: Brackman attributed its bump in circulation to its talent of “avoiding the peculiar occupations of the true underground.” It became apparent that Wilcock was ready for something edgier.

Krassner describes Wilcock during that time as “an imaginative journalist, always ahead of the curve, trying to link activists in various subcultures of the underground to each other.”

Thirty-nine years ago, Brackman attributed this to restlessness: Wilcock was discouraged from writing about Lenny Bruce and nudist communes, ostensibly because such subject matter was unfitting for a publication that advertised itself in The New York Times Book Review. Though the perceptive journalist had sensed a trend in the rising popularity of hallucinogens in the late ’50s, he felt forced to sit on the story.

But even as Wilcock grew displeased with the Voice’s relative conservatism, Krassner recalls the man’s kinship with the underground. “He plugged my magazine, The Realist, in his Village Voice column, the ‘Village Square,’ Krassner writes me in an e-mail. “He combined humor with information. He served as a missing link between the alternative world and the mainstream culture.”

Wilcock continued his weekly column in the Voice, and when the beleaguered publication could no longer afford to pay him, wrote “Village Square” pro bono, ensuring that his career as a columnist progressed uninterrupted while he pulled duty as a travel writer at a daily with a much larger circulation.

“I applied to every magazine, paper and ad agency,” he recalls. “The only people to give me an interview were the New York Times.”

Wilcock became one of five travel writers then employed at the paper, and when he decided to quit, three years later, he remembers the split having been “a mutual agreement.” “They were fed up with me — I kept a folded-up bike in the office, I smoked dope.”

He had veered from the Times in two remarkable ways: first, he was increasingly on assignment for Arthur Frommer to research travel books, and second, he had begun to edit the East Village Other, a pastime that effected his break with the Voice.

Krassner notes that approximately 10 years after Wilcock moved on, the Voice was sold to Rupert Murdoch for $7.5 million.

The Other, wrote Brackman in 1967, “is most aware of an international brotherhood of dissent, and underscores kinship with subterraneans in Paris, London, Bulgaria, Japan, India and elsewhere … while some of its colleagues are still talking Zen, EVO is into witchcraft, cannibalism, macrobiotics, astrology, aphrodisiacs, electric-charge machines, theocracia, existential psychotherapy and political independence (secession, emigration) for the underground.”

The EVO, in other words, was “decidedly psychedelic.”

“What a change that made in America!” Wilcock observes. “Before, people didn’t write about sex, didn’t go against government in any important way.”

The paper was financed by advertisements for record companies who wanted an audience of young people increasingly turned on to music as a tool for the revolution. According to Wilcock, the shrewd Jann Wenner, founder of Rolling Stone Magazine, successfully exploited this sentiment and ignited the downfall of the underground press.

“Wenner was smart enough to realize music was going to be the next big thing,” Wilcock explains. He charges that Wenner and then-CBS Records president Clive Davis made a bargain to pull advertisement from “troublesome,” oftentimes reactionary, underground publications.

“Whether by intent or accident, he undermined the underground,” Wilcock says of Wenner. “What were once underground papers are successful commercial alternatives.”

“I’ll give Wenner credit — he took over a lot of investing, political things that needed doing.” With a loaded simplicity, he adds, “The collateral damage was to kill the underground press.”

There will always be an underground, he adds, but, “There isn’t the idealism we had in the ’60s. There’s more selfishness.”

Extracurricular career activities

While EVO seemed more in tune with Wilcock’s politics, travel writing paid his bills, to some extent. Wilcock had been dining with his then-girlfriend when she happened to mention that Arthur Frommer was looking for a writer to assemble a guide to Mexico. In a dramatic gesture — as he remembers it — Wilcock put down his knife and fork and left his girlfriend by herself as he ran outside to make a call.

His employment with Frommer yielded not only Mexico on $5 a Day, but similar guides to Japan, Greece and India as well — a career that would take up the greater part of the next decade.

And on the side — there is, and has always been, an “on the side” aspect to Wilcock’s professional life — he had what he refers to as an apprenticeship to a witch named Elizabeth Pepper.

“We met accidentally on a subway one day. Somehow I just felt that I should know her,” he reminisces, quickly clarifying that the relationship was never anything romantic. “I realized she was a knowledgeable witch — the wise woman in the community [who] knows everything about cures and herbs and nature. She was a gourmet at the time.”

Together, they published The Witch’s Almanac, a yearly guide which promised information about moon cycles, planetary shifts and astrological influence. They also collaborated on a guide entitled Magical and Mystical Sites: Europe and the British Isles.

While gathering information both logistical and mystical, Wilcock continued to travel and work abroad, at one point estimating that he could “do” a country in 11 weeks.

Photos with famous people

After a brutal car crash in Greece left him hospitalized — “they told me I was never going to walk again” — Wilcock spent some time in forced self-reflection. “Not being able to read or do anything at all,” he says, “it really caused me to have a rebirth, appraise who I was.”

It may have been a turning point, but the chronology of it doesn’t much concern him. “It must’ve been the early ’70s,” he considers, “because I have a feeling that I broke up with my wife round about the early ’70s.”

As he lay recovering and taking himself to task in a London hospital, his friends in New York arranged a benefit to defray the cost of his medical care.

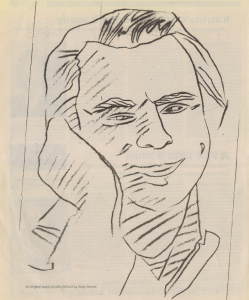

“Warhol did a portrait,” Wilcock recalls, “Abbie Hoffman was still on the run. He donated boots.”

Of the 1960s counterculture A-list that pops up in the anecdotes he shares of his years in New York, he remarks, “I was in a key place.” Wilcock’s celebrity allusions are natural in the course of the conversation; he is not at all fazed by the demigod status his old friends achieved in the years that followed.

“To tell you the truth, when I think back, I’m amazed at how little I realized what was going on. I was hanging around Warhol from the ’60s to about ’71. In all those years, I never really understood how significant he was or how important he was going to become.” He adds, “People were accessible in those days.”

He was their contemporary, after all: type-setting Steal this Book for Hoffman, offering Krassner his first joint, turning Woody Allen on to Dr. Jacob Moreno and the psychodrama movement, convincing Warhol to direct his creative energies into publishing (which resulted in Interview magazine).

In 1971, Wilcock published the humorously titled Autobiography and Sex Life of Andy Warhol as a very limited series.

A review by Branden W. Joseph of Harvard University credited the “virtually self-published” volume as a trendsetter in Warhol Studies, praising the “unassuming, slightly irreverent” tribute for the way it “cleverly engaged with Warhol’s self-fashioned image, reinforcing the impression that Warhol had nothing to say on his own behalf.”

For his part, Wilcock was astonished when a friend phoned to say that the book had been reprinted and was on sale for upward of $75 at some of the finer art museums in the world.

“It never really occurred to me they’d later become so significant,” Wilcock remarks of his iconic friends. “Take [Timothy] Leary. I’d resisted drugs for years. Mailer had offered me marijuana, I’d turned it down. My friend who ran a jazz magazine said, ‘Come and take these pills, it’s an experimental thing!’ I said, ‘I’m not into pills.’ He said, ‘This guy’s a professor at Harvard!’ ” Wilcock shrugs. “That began my life as a minor druggie. From ’61 to ’81, I probably smoked dope every day of my life.”

Having lived on both coasts, he found that New Yorkers were more apt to be productive with their weed use, using it more sparingly or only at the end of the day. In California, however, he sensed a more “wake and bake” mentality.

Wilcock has a friendly respect for marijuana, noting that in healthy moderation, it provides an affront to public service announcements warning of looming junkihood for all who light up.

“The analogy I use: It’s like a loom, it weaves all these loose ends together.”

“It’s an asset to the world and society,” he considers, “because if you can decide to do it and solve a problem with it — what’s the problem?”

Westward ho

There came a time, of course, when he had to move out west. With his marriage ending and an extended trip back to England growing distasteful, he says, “I did what a lot of Americans do — I started a new life in California.”

He wasn’t interested in San Francisco, so he headed to Los Angeles, where a former assistant helped him land a column in LA Weekly. One of his British acquaintances hooked him up with work for the London-based Insight Guides corporation, effectively making him West Coast editor of the travel book series.

“It got me back,” he says simply.

“I did 25 books of Insight,” he says. “What really saved me from starvation is my mummy died and left me her money.”

But, when money once again became tight, he took a garage apartment at Elysium, a nudist colony in Topanga. Although not necessarily a committed nudist himself, he lived there for 12 years, often leaving to cover a city or country for an Insight guide.

About a decade ago, he was invited to contribute as a weekly columnist at The Montecito Journal, and although he has never received a raise during his time there, he is content to keep his column running. Recently, he wrote to someone at Romenesko, a media industry news site, claiming to be “the longest-living, oldest columnist in America.”

No retirement

No retirement

Wilcock’s home is deceptively small, tucked away behind an unassuming house on a side street in Meiners Oaks. A dirt access road bends around to a cove of fruit trees, small flower garden and a wrought iron patio table, and inside, relics of his counterculture career sit among stacks of subscription newspapers and boxes of his newest publications.

Despite his flirtations with major press engines, the inexhaustible Wilcock is much like the hyperactive would-be poet who strings together chapbooks in his dorm at midnight. With self-publishing, he is in a way mirroring his earlier experiences in underground press: At the age of 78, he is creating the publication that he feels ought to exist.

The Ojai Orange, a monthly self-published zine, is subtitled “John Wilcock’s personal journal.” The layout, often on graph paper, shows an honest attempt at strict formatting, but the material is often too eclectic to fit within the confines of a small book, and often, blurbs are simply pasted down wherever they fall.

The man who can recall typesetting alongside an ornery Norman Mailer spends a couple of days a month literally cutting and pasting in a very tactile publishing process. At Wilcock’s home in Meiners Oaks, where the vintage Bohemian flow of his “hippie-style pad” is interrupted only by an iMac, he prints from 200 to 300 copies of his monthly collection of reflections, historical articles, cultural minutiae and explorations of personal obsessions (like the concept of invisibility). He is aided by a long stapler, a color printer and the Ojai Business Center.

“I love self-publishing,” says Wilcock. “I’ve been doing it since I was a child, even when I was at boarding school, 12 years old, I’d do little magazines and pass them around.”

The magazine is then made available to anyone who cares to have a subscription, in addition to a list he has assembled of “300 intelligent” recipients he wants to keep in the loop.

No sleep

And, as if he weren’t busy enough, Wilcock also films and produces a regular show on Ojai’s public access television station called Wait a Minute!

In the span of 30 minutes, he shows a collection of visual odds and ends, following the same philosophy he employs in his column: Give space to many items that wouldn’t merit an entire paragraph or show on their own, sandwich the provocative among the bland. For his weekly column, he scours Romenesko, reads the Los Angeles Times daily and the New York Times twice a week, flips through The Week and The Economist, and turns to trade magazines for tips on topics worth wider exposure. For his show, he films items of interest in sequence, bringing his camera with him for a quick sweep of scenery or an interview with whomever happens to show up at his place for coffee.

He also edits “in camera,” avoiding the hassle and cost of post-production and doing it the way he has since public access opened itself up to amateur producers in the early ’80s.

He travels often, and like a newspaper staff writer looking to expense every aspect of his trip, Wilcock squeezes as many shows and articles out of each journey as possible. During a recent cruise around the southern tip of France, he kept his hand-held digital video camera on and pointed at anything colorful or of interest. The bottom line, for him, isn’t a profit, or even breaking even. It’s filling his own personal magazine, or completing a worthwhile episode for public access television.

A trip to New Orleans yielded a cover picture and a lengthy article on absinthe, a very of-the-moment drink that, though illicit, is apparently all the rage among mixologists. A trip to Hawaii — “The one place where nothing’s going to happen,” he reasoned at the time — yielded a well-researched feature on the Ironman Triathalon for his April 2006 issue.

He often prints submissions from like-minded friends, although he laments that few of them come from Ojai. For the lively intellectual subculture Ojai seems eager to represent, Wilcock found few people interested in collaborating with him on a monthly publication that stood to make little or no profit.

“There’s something about Ojai …” he considers, trailing off. “There’s not a lot of conversation. I’m always looking for people interested in ideas, concepts. The majority is not really interested in getting out of the box.”

“I’m used to going to art openings, knowing hundreds and hundreds of people — there’s no doubt,” he says of his old stomping grounds, “New York is the center of the intellectual, English-speaking universe.”

He adds, “Somebody once said, ‘You lose one IQ point for every year you’re here [in California].’ Someone else said, ‘That’s ridiculous! 10 IQ points!’ ”

Still, his zine is a delightful compendium of trends, either external or in Wilcock’s own consciousness. His trip to the island of Milos inspired him to research the mutilated statue of Aphrodite. Similarly, his sudden curiosity about the head of the Roman Catholic Church led him on a research binge that ended with his Popes and Anti-Popes, with 150-200 words about every pope in history, published by Xlibris last year.

He eschews the Internet in most cases, finding that, as a research tool, it’s, well, crap. Much of the information he comes across is “unattributed,” as he so diplomatically puts it.

While he worries that the Web is degrading journalism, “the Yorkshire man who went to the states and created underground press,” as he has been called by British journalists, embraces the opportunity to put his “oeuvre” online. He is working on streaming his shows, archiving his columns, and currently has all back issues of the Ojai Orange available.

Among a library of 40 of his glossy, published books, a print of Wally Wood’s “Disneyland Memorial Orgy” as published by friend Paul Krassner hanging in the background, the talkative Wilcock is thoughtful. Without dipping into the morose — the man who witnessed the tumult of the 1960s from the best possible vantage point is nothing if not balanced — he repeats a simple desire: for a good editor “with sympathy in that subject” to help him make something more cohesive of his autobiography, for a female partner to travel with (“I’ve never found one”). If he could get both in one package, so much the better.